It’s the end of the day. You still have so much to do. You have accomplished a lot, but looking at your to-do list, it feels like you should have been able to accomplish more. You have to approve the ad campaign marketing a new service. You have a class to attend tonight. You need to create a keynote speaker presentation for a client, and you are sitting in front of your computer, unable to think about how to make the next slide in your presentation. Looking at your clock, you decide to skip the gym and use the time to keep working. You just want to get this done. Determined, you press on.

If this is you, your strategy needs an upgrade.

As children, we were often told to finish our homework before being allowed to go outside and play. In school, we might have had to stay in from recess if we hadn’t completed an assigned task as instructed. In high school, perhaps we received detention for missing assignments. We learned in order to play, we had to get our work done. It can be argued that this strategy, even for children, is seriously outdated. More importantly, if you are in your 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s, or 70s and still have this strategy in play, this article may change your life.

It’s easy to tell children to do their work first so they can play. We want children to learn how to delay gratification, develop study skills, and persevere when challenged. Of course, children aren’t running small businesses, married, or needing to figure out what the family will eat for dinner tonight.

The idea that you have to finish all of your work before you can play is absurd, and yet, think about the last time you threw yourself into “detention,” perhaps deliberately missing a yoga class so you could complete one more thing. As adults, our play is spending time outside, exercising, connecting with others, reading, working on a jigsaw puzzle or traveling. Without play, without connection to our lives, we lose access to our best selves.

Burnout continues to be a concern for all, especially for entrepreneurs and leaders. While identifying the microstress chipping at our resilience, work/life balance is sought after in hopes of bringing a more well-rounded experience of life. Figuring out life hacks on how to focus our brains when we need our brains to be creative or complete an assigned task. These issues are important, and while there are many ways to address these, I wonder if we aren’t missing the most significant part, developing a new strategy focusing on science.

As adults, entrepreneurs, leaders and individuals with ADHD, our to-do list is never complete. Our work is never done. Living underneath the rule of a childhood strategy of work first and then play would mean we would never get to play, relax, or experience satisfaction from our daily accomplishments or small wins. It means that even when we have accomplished important tasks, we may still feel the strong pull to complete one more thing from our list in exchange for making it to our yoga class on time. Doing this once in a while may be necessary; however, when it is your approach to the majority of the challenges you face day in and day out, you become your own barrier to you accessing your greatest moments of creativity, productivity, and, frankly, overall wellbeing.

It doesn’t help that the term work/life balance brings up a visual of a perfectly balanced seesaw with work clearly defined on one side and life on the other side, suspended, weightless, on an apex of uncontrollable life events happening moment to moment. This concept of work/life balance becomes only accessible to the few, instead of the masses. We wonder, what is wrong with us that we cannot achieve this idea of work/life balance. Feeling like we should have, could have, would have, but didn’t because there weren’t enough hours in the day.

Now just to reset expectations, I wonder, when was the last time you heard anyone brag that they finally figured out work/life balance? It begs the question, is work/life balance even attainable or is it another fantasy of the mind, like perfection? What if we were looking at this the wrong way? What if instead of work/life balancing itself perfectly, we looked at the integration we seek as work/life flow? Picturing work/life as movement, instead of a moment of balance, may help us create a strategy aligned with how our brains work.

Think of the number eight (i.e. 8). If the top half is work and the bottom half is life, we travel from the top to the bottom and back up to the top, indefinitely. Bringing presence to wherever we are. So when we are working, we are present. When we are with family, we are present. This movement better depicts work/life flow or work/life integration or real life with its unpredictability.

In addition to proposing work/life flow as being fluid, flexible, in motion and responsive, consider that all of life exists in a fluid state, including our productivity, creativity, and problem-solving ability. We think we can command ourselves to be creative just because our schedules state the next three hours are dedicated to being creative. This is not how our brain works. We require breaks to be our best. We require play in order to access our creativity. Noticing when our strategy no longer serves us and being mindful of what our brain and our body are telling us is a good place to start.

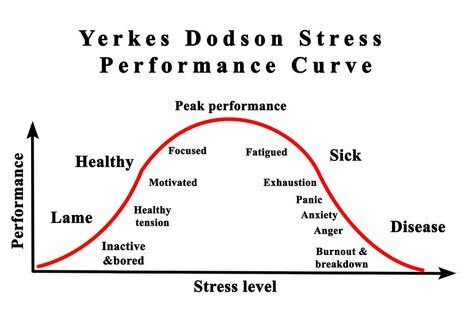

Consider the Yerkes-Dodson Human Performance and Stress Curve. We are at optimal peak performance at the height of the bell curve. Once we become fatigued, we would be better served to take a break and play (i.e. exercise, go for a walk, step away from the desk, watch something funny, send that something funny to a colleague). This is the point where the old childhood strategy of finishing your work before you play is actually creating barriers, preventing you from being as efficient as you could be.

In an article called, “Let’s hear it for the four-hour working day” by Oliver Burkeman from The Guardian, Burkeman focuses on the book “Rest: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less” written by Alex Pang. Oliver mentions that the perfect number of hours to do creative work is four hours a day. He reminds us that this doesn’t mean you complete four hours and sit on the couch for the remainder of the day; instead, it is about understanding that we need breaks from our work in order to return to our work refreshed and capable of being productive.

Consider the following working schedules mentioned in Pang’s book and in Burkeman’s article, “Charles Darwin worked for two 90-minute periods in the morning, and then an hour later on; mathematician Henri Poincare from 10am till noon then 5pm till 7pm” (Burkeman, 2014, para 2). Quoted by Burkeman, Adam Smith stated, “The man who works so moderately as to be able to work constantly not only preserves his health the longest but, in the course of the year, executes the greatest quantity of work.”

In the article, “When, how, and how often to take a break,” written by Neil Patel, Patel mentions, “The United States Army research institute discovered that ultradian rhythms have 90-minute cycles.” He counters that some individuals even with a 20-minute break in between 90-minute sessions, may find a 90-minute work session challenging; he recommends the Pomodoro technique, working for 25 minutes, taking a 5-minute break, and after four cycles taking a 15-minute break. While Patel also mentions research done by Desktime where it was found that a 17-minute break every 52 minutes was the sweet spot for productivity” (Patel, 2014, para 13).

So instead of skipping the gym, let go of the “shoulda, coulda, woulda” conversation and implement a new strategy for life. A strategy that includes listening to our brain and our body for the messages it sends us when tired. There is no doubt, if you continue to implement the childhood strategy of working first then playing, you are spending much of your time frustrated while being unproductive.

Having an unconscious approach to life is a strategy for burnout. And while the strategies we create may work for years or maybe just for a season, we need to reflect on whether our current way of being is really, really supporting our success. Your resilience, creativity, and productivity depend on how you spend the hours of the day. Afterall, we only get 24 hours in a day.